Creation and Serendipity: Svend Andersen’s Early Days

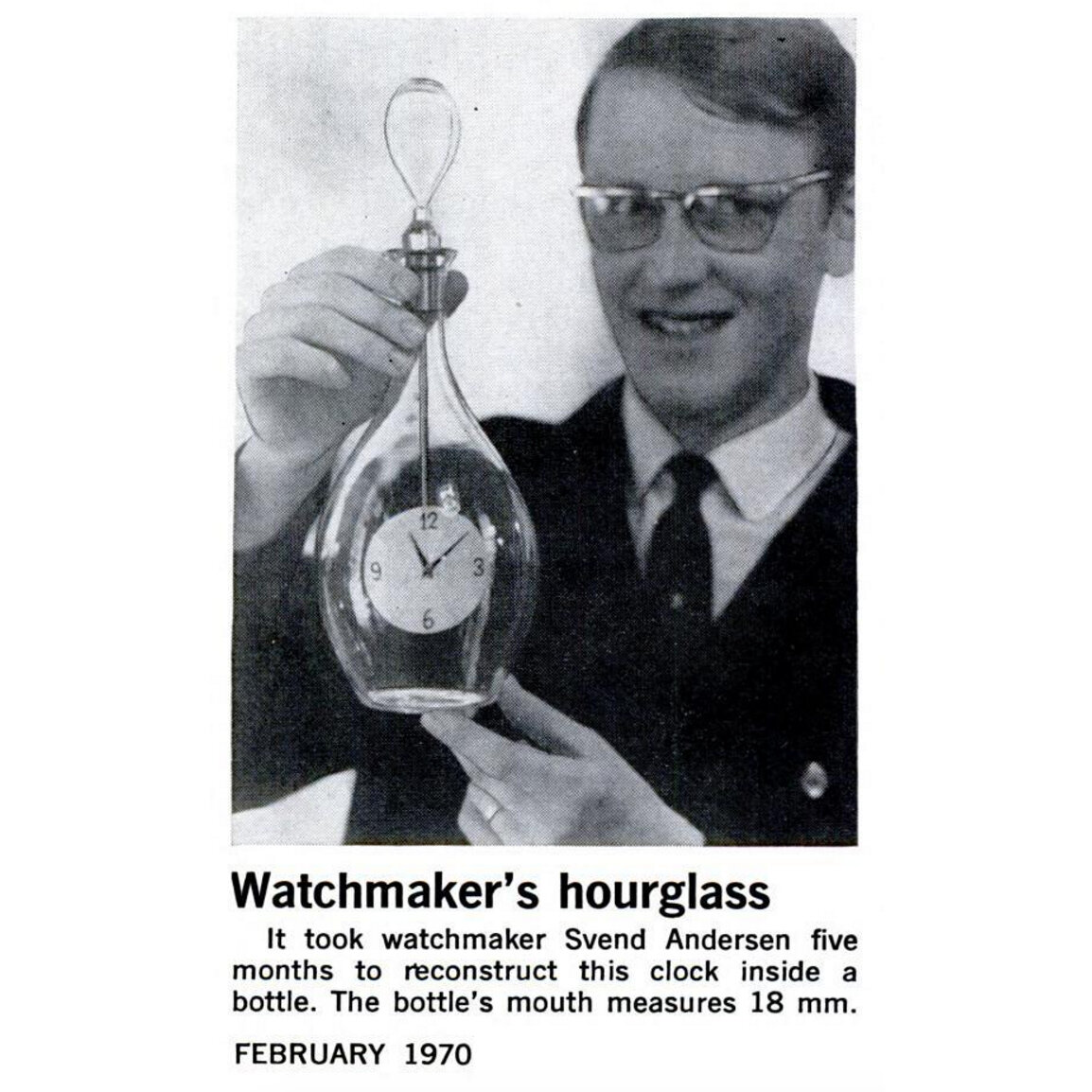

“After celebrating New Years Eve, I woke up and saw the time on my clock through an empty bottle from the festivities,” Svend Andersen said and chuckled. “And that’s when I first asked, can you put a clock in a bottle?”

Every beginning is improbable, the result of chaotic circumstances coming together at the right moment and time. In the case of Svend Andersen and his long, illustrious journey as an independent watchmaker, some spirited New Year's celebrations in his youth put the young watchmaker on the map. This unimaginable inspiration led to the creation of his Bottle Clock in 1969. When showcased at the "Montres et Bijoux" Show in Geneva, he received critical acclaim almost immediately. Akin to virality on the internet today, publications, televisions, and the word of mouth amongst collector circles spread at the speed of sound. From a groggy check of the time on New Year’s Day, the Bottle Clock became the launch pad of Svend’s watchmaking journey.

Now for those who aren’t overly familiar with Svend, there are very few other independent watchmakers who have been in the game longer. He was one of the co-founders of AHCI in 1985, and has been independent since 1980. With the privilege of a long history, Svend is a master storyteller as much as he is a master watchmaker. And that’s why we reached out recently. We wanted to hear the story of how he originally found inspiration for the Bottle Clock, how he made the transition to being an independent watchmaker, and ultimately what kept him busy during the early period of his career. What came from this discussion is the story of how creation always opens doors in unusual and unpredictable ways.

Svend’s arrival on the map

While the Bottle Clock gathered critical acclaim, Svend was still working as a watchmaker in after-sales service at Gübelin in Geneva. It’s then that Patek Philippe representatives walked “across the street,” as he described it, and plucked him to work in the maison’s Grand Complications workshop. At that time, the logic of the hire was fairly straightforward: if Svend could figure out how to assemble a clock inside of a bottle after working hours from the confines of his bedroom, he probably had what it takes to handle complications with a high degree of competence. If time is an indicator, the rationale for this decision panned out. For nearly a decade, Svend worked with Patek on the restoration and servicing of some of the most exquisite, complicated timepieces in the world.

As a “side hustle,” the Bottle Clock was very much still a thing, keeping him busy through the early 1970’s. In total, he sold 38 Bottle Clock’s with some fascinating clients along the way. Namely, the Ripley’s Believe It or Not franchise purchased a handful of these timepieces to display at their museums across the US. The remaining Bottle Clocks were sold to collectors, either directly or through retailers like the venerable Beyer in Zürich. Though still at Patek Philippe, the Bottle Clock project led Svend to develop relationships that your average in-house watchmaker would not normally possess, especially in the pre-internet era where tapping into collector circles was far less easy. Relationships with retailers and collectors alike, through the Bottle Clock creation, paid dividends over the remainder of his lifetime of watchmaking.

Mr Svend Andersen

By the end of the 1970's, circa 1977-78 as Svend recalls, the Quartz Crisis knocked the luxury watch industry on its side. Svend found himself with his hours cut at Patek Philippe, working only 2 days weekly. It seems absolutely preposterous today to think of Patek Philippe in such a situation, but at the time, that’s all the business had for payroll during the industry-wide slowdown.

Meanwhile as the work came to a grinding halt, a Swiss-German collector approached Svend with a Louis Audemars pocket watch movement- complicated, well preserved, yet missing its gold case. At some point, as was fairly common, the gold case was sold during WWII or under difficult financial circumstances for sheer survival purposes, while the movement, relatively devoid of fungible value, was kept in the family. It’s then that the collector asked a question that would further push Svend in the direction of his career to come: "When you can put a clock in a bottle, can you not recreate a case for this movement?"

While Svend didn’t have an immediate answer to this question, he did have the time to figure it out. So at the height of the Quartz Crisis with limited working hours at Patek Philippe, Svend spent his off-days in the library, researching pocket watch case designs and manufacturing processes. As he mentioned, “I had three children at home and not much work. I was looking for something to pursue.”

Ultimately, he designed the case and partnered with a casemaker to deliver on the collector’s request, or challenge depending on how you look at it. Like the Bottle Clock beforehand, the finished case caused a frenzy at a local collector meet-up in Munich in the late 1970’s, leading to a wave of similar requests from collectors. It should be mentioned here due to the economic circumstances of the time, the idea of independence, leaving Patek Philippe to launch a workshop, didn’t simply “make sense” because of collector demand - it was the only decent opportunity on hand.

Opportunities, especially in crisis

Svend left Patek and opened his own workshop on January 1, 1980. The beginning of a new decade, the beginning of a new venture. Initially, the first few years were dedicated to pocket watch cases with collector after collector lining up to re-case movements. As he mentioned though, “the supply of high quality pocket watch movements ran out by around 1983-84.” To design and manufacture a gold case for such complicated movements was often a 10,000+ CHF affair, meaning there were only so many movements of other-worldly quality that would ever merit such a large investment in a case.

Sven Andersen’s Communication Early Edition (Source: Instagram.com/andersengeneve)

Yet even as things shifted gears, this initial period leading to and occupying the beginning of Svend’s “independence” was fundamental to the overall development of his later watchmaking career. As Svend said, diving deep into pocket watches trained his eye on design and honed his knowledge of horological history. What started with a question and research in the library continued for 5+ years, leaving Svend with a broad familiarity with the design and mechanical differences across English, Swiss, German, and French aesthetics and approaches to watchmaking. Interestingly, it wasn’t until almost a decade after he launched his own workshop, in 1989, that Svend produced the first “Svend Andersen” timepiece - the World Time on a 24 timepiece souscription.

Sven Andersen Communication in yellow gold from the 90s (Source: Instagram.com/andersengeneve)

So what is there to make of Svend’s early years as a watchmaker? Well in the 20 years between the New Year’s Day inspiration for the Bottle Clock and his first wristwatch, we can only say that his journey can only be characterized as serendipitous. From the twists and turns of the Bottle Clock to Patek Philippe to the Quartz Crisis to a collector’s request for a good pocket watch case, each step is born of chaos or fate. There is one common thread to be found throughout this commotion though, an organizing principle if it were: Svend was always willing to go outside of his comfort zone and that risk reaped great rewards.

And why that willingness exists, that’s difficult to know.

Maybe it was his forward-facing role, interacting directly with customers at Gübelin early in his career or his ability to navigate different cultures and languages smoothly, or maybe it was something about being between different places from a childhood on the border of Germany and Denmark, all could give some answer as to why Svend possesses an unrelenting openness to say yes to serendipity. After all, he would have never received the title, “the watchmaker of the impossible,” had he said no to the Bottle Clock, no to the gold pocket watch case, no to the world time complication.